Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

Street Racing

Guide No. 28 (2004)

by Kenneth J. Peak & Ronald W. Glensor

Translation(s): Sokak Yarilari (Turkish)

The Problem of Street Racing

The guide begins by describing the problem of street racing and reviewing factors that contribute to it. The guide then identifies a series of questions that might assist you in analyzing your local street racing problem. Finally, the guide reviews responses to the problem and what is known about these from evaluative research and police practice.

While street racing and cruising share some common characteristics, there are important differences between the two activities and those who participate in them.† Cruising typically involves an older crowd, and is a highly public and largely nostalgic event that is often confined to downtown areas. Cruising can also provide an economic boost to the community.†† Street racing typically involves a younger crowd that conducts its activities in an underground fashion to avoid police attention and presents significant risks of serious personal injury.

† See the Problem-Specific Guide No. 29, Cruising.

†† Northern Nevada's "Hot August Nights" event, for example, generates $132 million for the Reno and Sparks economies, and brings more than a half million people to the area during the weeklong event (RRC Associates, 2003).

Related Problems

Police must also address other problems related to street racing, which are not directly addressed in this guide . Other problems that may call for separate analysis and responses include:

- Auto theft†††

- Assaults (including assaults in retaliation for failure to pay racing bets1)

- Cruising

- Curfew violations

- Drunken driving and driving under the influence of drugs

- Gang-related activity

- Insurance fraud (relating to racers betting on outcomes)§

- Illegal vehicle modification (e.g., smog control alteration)

- Illicit gambling

- Noise complaints

- Public intoxication/urination and other public order offenses

- Theft and fencing of auto parts

- Thefts from autos

- Trespassing

- Vandalism and littering

§ For example, a racer wagers his car's racing wheels or custom seat covers and loses; he then files a police report and insurance claim stating the items were stolen in order to obtain a new set; or, a racer who blows an engine will abandon the vehicle and then report it stolen, to acquire money for a replacement (Sloan, 2004).

The American street-racing tradition dates back to the 1950s, and has long been a staple of Hollywood movies, including films such as "Rebel Without a Cause" (1955), "American Graffiti" (1973), and "Grease" (1978). But no movie did more to boost the popularity of street racing than the 2001 surprise hit, "The Fast and the Furious," which grossed nearly $80 million in its first 10 days in theaters and includes spectacular racing scenes and daring stunts (including one where a car swerves back and forth beneath a speeding tractor-trailer).2 Although the movie studio issued public service announcements that encouraged safe and legal driving, the film likely provided fresh inspiration to street racers.†

† A 78-year-old man was killed in Los Angeles by a speeding driver who had just seen the movie, and in Redwood City, California, officers arrested six men caught racing down Interstate 280 at more than 120 miles per hour; all had ticket stubs from the film in their pockets (Squatriglia and Nevius, 2003). I n San Diego County, California, where the movie was made, 15 people were killed in racing-related incidents in the year after the movie's release ( Reno, 2002) .

The street racing population consists of several distinct demographic groupings. One is estimated to be between 18 and 24 years of age, generally living at home and typically having little income.3 Another group involves predominantly older (25 to 40 years of age) white males who engage in building and racing the older types of "muscle cars:" Corvettes, Camaros, Mustangs, and so on. Asian and Hispanic males of a wide range of ages and driving later model imported cars—such as Hondas, Acuras, Mitsubishis, and Nissans—are another group.4 Presently, the latter group dominates the street racing scene.5

Credit: quebecstreetracing.org

Police suspect that many racers engage in illegal activities in order to finance their hobby; some agencies report that stolen vehicles have been stripped of parts that were later recovered from street racing vehicles.6

Whether by lawful or unlawful means, many racers feel they must devote huge sums of money to "soup up" their race cars; a major upgrade, with supercharger blowers, nitrous oxide systems, and other high-performance equipment can easily exceed $10,000.7For many racers, getting the maximum performance out of their cars is very important to them and they will expend a tremendous amount of time, money, and effort toward that end.8

How dangerous is street racing? Data are difficult to obtain, because neither the federal government nor the insurance industry tracks related casualties, nor is software yet available for creating a database of street racing.9 However, measures are being taken in some jurisdictions to address this shortcoming and are discussed below. One unofficial estimate, derived from examining news reports and police data from 10 major cities and extrapolating on the basis of national population figures, is that at least 50 people die each year as a result of street racing.10 Although related deaths are difficult to quantify, media reports confirm that street racing takes its toll on innocent people as well as street racers, passengers, and onlookers.

At the root of the problem is the fact that youths have always had, according to one scholar, a "profound need for speed."11 This love of speed is not restricted to the youth of the United States; indeed, the problem has reached serious levels in Canada, Australia, Germany, England, France, New Zealand, and Turkey.12 In Canada, where a Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer was killed by a racer in 200213 and another 18 people died in the Toronto area in street racing incidents during a four-year period,14 a new law was introduced in which street racing is an aggravating factor when sentencing persons convicted of dangerously or negligently operating a motor vehicle.15 In Vancouver, British Columbia, street racing can include an activity known as a "hat race," also known as a "kamikaze" or "cannonball run," in which drivers put money in a hat; the money is taken to an undisclosed location from which a call is made, informing the drivers where the cash awaits. The first driver to get there wins all the money. Pedestrians have been killed during such races.16

Credit SDStreetracing.com

Today in the United States, the racing tradition replays itself during every weekend in thousands of communities in the nation. The primary difference today is that street races are extraordinarily brazen and elaborately orchestrated functions, involving flaggers; timekeepers; lookouts armed with computers mounted in their cars, cell phones, police scanners, two-way radios, and walkie-talkies; and websites that announce race locations and even calculate the odds of getting caught by the police.17 Some websites even provide recaps of the previous night's races, complete with ratings of police presence, crowd size, and a link to the police agency so the curious can see if a warrant has been issued for their arrest.18

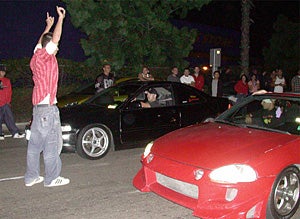

Street races typically involve racers and spectators meeting at a popular gathering place, often on a relatively remote street in an industrial area. Here they decide where to race; they then convoy to the site, where a one-eighth or one-quarter mile track is marked off. Cars line up at the starting line, where a starter stands between them and drops his or her hands to begin the race. Several hundred spectators may be watching. Unlike racetracks that allow spectators to observe races in a safe, closed environment, these illegal street races encourage spectators to stand near possibly inexperienced drivers and poorly maintained vehicles—a combination that can be deadly for onlookers standing a few feet away from vehicles racing at highway speed.19 Other peripheral activities may be involved as well. For example, racers and spectators engage in what are termed "sideshows," such as using vehicles and onlookers to block off an intersection and thus backing up regular vehicular traffic for considerable distances and preventing the police from arriving at the scene; then the racers at the intersection engage in 360° burnouts, races, and so on.20 Racers also participate in what is termed the "centipede," where they form a convoy of vehicles and play follow-the-leader, darting in and around normal traffic at high speeds. Or, they may speed around corners to see how far they can slide their tires.

Street racing can also be unorganized and sporadic in nature, involving impromptu, one-time races between persons who do not know one another; the police generally have little means for dealing with these types of racers other than utilizing the media to make it very clear that, if caught, the violators will be severely prosecuted.21

The specific harms caused by street racing include:

- Vehicle crashes (deaths and injuries to drivers, passengers, onlookers, or innocent bystanders; and property damage)

- Noise (from racing vehicles and crowds)

- Vandalism and litter at racing locations (including businesses where racers commonly gather)

- Loss of commercial revenue (if racing crowds obstruct or intimidate potential customers)

- Excess wear and tear on public streets (painted street markings commonly are damaged by the burning rubber of vehicle tires)22

Credit: Marion ( Ind.) Chronicle-Tribune

Retaliatory offenses may also occur, such as when citizens try to deal with the problem themselves by placing nails on the ground where racers congregate or vandalizing racers' cars, for example.

Factors Contributing to Street Racing

Understanding the factors that contribute to your problem will help you frame your own local analysis questions, determine good effectiveness measures, recognize key intervention points, and select appropriate responses.

There are several reasons why street racing can become, or remain over time, a popular pastime in a community:

- It provides an unsupervised activity and environment.

- It attracts people who are too young for bars or other adult-only activities (especially in cities having a dearth of alternatives for their youth).

- It affords a means of socializing with friends.

- It provides a means of showing off one's motor vehicle and driving ability.

- It provides drivers, passengers, and onlookers the exhilaration of speed.23

Roadway location and design can also contribute to street racing. For example, a roadway located in a remote, perhaps industrial, area that is straight, wide, and close to arterial streets (for quick getaways from the police) will be favored by street racers.24 The existence of car clubs and/or gangs in an area can also create or exacerbate a community's street racing problems.25

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Street Racing

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

Your E-mail *

Copy me

Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.