This guide deals with the process of implementing responses to problems in problem-oriented policing (POP) initiatives. It addresses the reasons why the responses you plan to implement do or do not get properly implemented, and how you can better ensure that they do. The guide does not address the broader issues relating to implementing a problem-oriented approach to policing within a police agency, matters that have been more fully explored elsewhere. 1

The POP literature has paid a fair amount of attention to the processes of analyzing the nature and extent of problems and developing suitable responses to them. Relatively little attention has been paid to the actual process of implementing the responses, and to the factors that are important in getting it right. 2 It is clear from POP studies, however, that implementation failure is common.

Implementation takes place in the "response" phase of the SARA (Scanning, Analysis, Response, Assessment) problem-solving model. The response phase actually comprises at least three different tasks: (1) conducting a broad, uninhibited search for response alternatives; (2) choosing from among those alternatives; and (3) implementing the chosen alternatives. 3

There are four basic reasons why any particular problem-solving initiative might fail:

This guide concerns itself principally with the third of these four reasons: successful or failed response implementation.

The guide is divided according to the four key stages of implementation:

Bear in mind that POP initiatives are of varying scope and complexity, ranging from highly localized projects that a lone police officer might address as part of his or her routine duties, to ambitious projects affecting the entire jurisdiction that require a team of specialists to address. Therefore, the factors and recommendations discussed here will have more or less importance, depending on the POP initiative's scope and complexity.

You must take into account a range of factors before beginning the implementation process. In some cases, these factors are a given and cannot be influenced. Understanding these will help in selecting responses and in planning how you will implement them. In other cases, you can alter the factors to generate a more satisfactory outcome from an implementation perspective. Regardless of the type of factor concerned, they help to set the context within which future implementation will be undertaken.

There are six key factors that you should take into account before starting implementation: 4

Each of these factors is discussed in the following pages.

Responses are more likely to be implemented where there is clear support for them within the organization undertaking the implementation. This is particularly important where an organization is expected to invest resources in an initiative. Here, there are a number of questions that you should ask that may affect internal support:

You should consider each of these issues before starting an initiative, as a lack of organizational support could make it more difficult to win the necessary resources and colleague support to complete the work required. It is also important to bear in mind that internal support will also be helpful if there are subsequent implementation problems–especially problems involving external partners or the local community.

While it is important for the initiative to have the support of the organization responsible for its implementation, it is equally important to win the support of the specific people tasked with delivering the initiative. In the context of implementing POP initiatives, it is desirable that the people needed to implement responses feel some sense of ownership of the action plan. 5 You can cultivate a sense of ownership in key people by providing them with opportunities to influence the project's direction, such that they feel they are not merely implementing somebody else's plan, but implementing their own. Conversely, a lack of input by key people at meaningful project stages can lead to their lack of commitment to implementation. 6

Ideally, the same people should remain actively involved throughout a project, from initial problem identification to analysis to response development to response implementation to assessment. Ideally, those who spearheaded the problem analysis would have the capacity and desire to put their resultant plan into action.

In some cases, action plans are developed without the input or commitment of those who will be tasked with putting the plan into action, such as professional grant writers, whose role is to bid for external funding. This obviously can have a detrimental effect on winning ownership for an initiative if it is felt that the solution to the problem is imposed on those tasked with carrying it out.

Where it is impossible for the lead problem analysts to implement the action plan, the next best possibility is for the plan to be officially assigned to one or more people who will be held accountable for carrying it out. When responsibility for implementing an action plan is neither assumed nor assigned, the plan typically lies dormant.

The lead researchers of the earliest POP initiative examining the problem of drinking drivers concluded that the failure to fully implement the recommendations for action arising out of the inquiry were largely attributable to the fact that no one person within the police agency had or was given responsibility for doing so. 7 By contrast, the recommendations for action that emerged out of the same researchers' analysis of a second problem—repeat sex offenders—were promptly and effectively implemented owing largely to the fact that a police lieutenant was tasked with doing so. 8

A sense of ownership of a response plan is unlikely to be created merely by assigning it to someone, or by providing extrinsic motivations such as financial reward. For example, where police officers or others agree to carry out certain assignments principally because there is overtime compensation to be earned from doing so, it is often the case that the commitment to carrying out the plan as originally designed is weakened.

Just as internal support is essential to successfully implement a response, so too is external support. There are potentially a number of sources from which you might obtain external support.

In some cases, you can implement responses without requiring external organizations’ support or cooperation, using the police agency’s internal skills and expertise. However, increasingly, multifaceted initiatives involve working with other partner organizations, drawing on their particular mandate and expertise to complete aspects of the required work. 9

In engaging with partner organizations whose support is essential, it is important to take into account the culture, perspective, objectives, and performance indicators under which the organizations operate. 10 Partnership-working is likely to be most successful where there is mutual benefit from engaging in an initiative. Therefore, you must understand how an external organization is likely to receive involvement in a given response and, where necessary, sell the benefits of involvement in their own terms. Indeed, responses are more likely to be implemented if the people and organizations tasked with implementation feel they are competent to carry out the activity, one that fits their conception of what they or their organization should be doing. For example, police are more likely to conduct criminal law enforcement activities because such activities fit squarely within the scope of police competence and self-image. They are likely to be more reluctant to engage in other sorts of tasks, such as providing social services. So, too, with other agencies. The Boston Gun Project, which comprised an interagency task force, appears to have apportioned the various tasks that were part of its overall response plan in accordance with the participating agencies' respective competencies and self-images. The police engaged in enforcement crackdowns, the clergy and gang outreach workers offered aid to gang members, probation officers supervised their clients, prosecutors prosecuted crimes, and so forth. Responses were faithfully implemented perhaps in part because no agencies or people were asked to stretch their conventional sense of their own function. 11

In other circumstances, an organization may undertake an initiative without taking into account the existence of other organizations delivering similar interventions in a similar area. In the United Kingdom, police target-hardening of burglary victims’ homes, undertaken under the auspices of the Home Office-funded Reducing Burglary Initiative, sometimes conflicted with the work of local charities that were target-hardening the homes of vulnerable people (including burglary victims) in the same areas. It is therefore useful to consider who else is undertaking similar interventions for the same target area/group and to engage them in participating in the initiative, rather than setting up new structures that end up competing for the same intervention recipients. 12

Response plans that enjoy grassroots community support tend to be more likely to be implemented than those without it because you can convert such support into political influence, which can mobilize resources and action. Indianapolis police could sustain an intensive effort to stop vehicles, search for guns, and investigate suspicious drivers and occupants in a predominantly minority community owing in large part to police preparatory work to gain community understanding of and support for the initiative. 13

Before implementing a response plan, you should consult with those community members whom the action will most affect. This may include active forms of consultation, such as community meetings and meetings with key community representatives, and more passive forms of consultation, such as letters to local community members informing them of the response plan. The response plan’s effectiveness may depend in part on this consultation. 14

When media coverage of an initiative presents the police agency in a favorable light, it can provide a substantial boost to response implementation in several ways:

Media coverage, however, is not universally supportive of initiatives to address particular problems and can, in fact, thwart them. When Lauderhill, Fla., police filed a nuisance abatement action against a commercial property owner as a means of controlling an open-air drug market operating on the property, local newspaper coverage was hostile to the police action, adopting the editorial view that only drug dealers and buyers should be held responsible for the drug market, not the property owner, and further questioning police motives. Although the adverse media coverage did not ultimately hinder the legal action, it did weaken public support for it. 15

Leadership associated with the project is key, both in terms of the person taking an initiative forward and in terms of the implementing organization as a whole. Where individual project leadership is concerned, it is often cited as one of the factors influencing response implementation. 16 Indeed, it often seems that a strong leader can make a success of even the weakest of responses due to his or her diligence, persistence, and perseverance in the implementation process. These people schedule and lead meetings, perform the tasks they have agreed to and hold others accountable for doing the same, and generally do whatever is necessary to keep the project a priority concern. These people often exercise a degree of leadership not commonly expected of their rank and position. They press ahead unless made to stop. This highlights the importance of carefully selecting a project leader. It should not simply be a matter of who can spare the time, but rather who is best for the job, preferably with a track record for delivering on past projects.

Where organizational leadership is concerned, response implementation can be assisted by strong senior management leadership. This can provide support and encouragement for a project, as well as address high-level problems should the need arise. It can also be beneficial where high-level policy changes are involved. This was exemplified when the Fremont, Calif., police chief spearheaded his agency’ initiative to change its response to burglar alarms. In the face of strong alarm-industry opposition, the chief pressed the case for a policy change by carefully presenting his agency’s internal analysis of its response to burglar alarms to alarm owners, elected officials, and the public at large. 17

In police agencies in which initiative is not encouraged among the lower ranks, POP projects can fail because the higher-ranking executive officers on whom project leadership depends can become easily distracted by other pressing concerns. The lack of engagement by high-ranking officers at critical junctures in the project can mean that the project achieves less than it might otherwise.

Good senior management leadership should also help to create an organizational attitude in which failure is acceptable, but where failing to try isn’t. Organizations with a strong blame culture will stifle innovation and creativity by making staff wary of trying something new, for fear of being seen to fail.

Good communication is essential with all parties involved in a project. From the outset, all parties should be aware of what is expected from them, and differences of opinion should be addressed early on, before they adversely affect people’s relationships.

Communication associated with an initiative needs to be multidirectional and possibly involve different messages for different groups. Those with whom communication should be undertaken include

From the outset of a response, it is important to have in mind the resources available to complete an initiative. All responses will be subject to four key constraints: time, costs, other resources, and quality. Where time is concerned, there will usually be a deadline by which the response is expected to be completed. “Costs” refer to the financial expenditure or “hard cash” associated with the implementation. In many responses, some cash must be expended in the process. “Other resources” refer to the myriad other things that an organization can bring to a response. These will include staff time, office space and equipment, vehicles, etc. These are often viewed as free from the organizational perspective, but are subject to an opportunity cost—if they were not devoted to implementing this response, they could be used for other purposes. “Quality” refers to how the response is completed and how thoroughly a job is done.

From a resource–allocation perspective, there will be trade–offs among these four constraints. For example, a job may be completed in a shorter time if more other resources are devoted to it. Alternatively, a response may be completed at a lower cost by reducing the quality of the work that is acceptable. From the outset of implementation, it will be important to keep in mind each of these constraints, which will reflect the resources available.

While initiatives are often provided with time and other resources, there is often a problem with accessing working capital required to pay for the project's running costs. This could be because there are insufficient funds available or the administrative mechanisms that govern public organizations’ expenditures stifle the ability to make timely purchases. An evaluation of the U.K.’s Arson Control Forum’s New Projects Initiative found that while the funding had allowed local fire and rescue services to recruit arson task forces, some couldn't implement initiatives due to a lack of funds. 18 By contrast, some of the arson task forces leveraged in significant additional funding from partner agencies by offering some funding themselves.

There are a number of issues associated with staffing that need to be addressed from the outset. These include

Each of these is discussed in turn below.

Creating a specialized assignment to address a problem appears to increase the likelihood that action plans will be implemented. Specialized assignments might be in the form of special task forces, specialized units, detachments, and other similar arrangements. The specialization of the assignment might be either to the particular problem or to some sort of problem–solving unit within which the people assigned can choose problems to address and concentrate their work on them. Among the most successful POP initiatives, one more commonly finds them occurring within the context of specialized rather than generalized assignments.

Typically, specialized assignments provide not only the time and other resources necessary to the task, but also they often yield greater accountability because responsibility for addressing particular problems is more firmly established. Specialized assignments can also prevent staff from being used for other duties by protecting them as a dedicated resource.

Additionally, specialized assignments offer other intangible benefits to the people assuming those assignments: prestige, freedom from ordinary duties, greater autonomy over working conditions, and so forth. To the extent the people value these benefits, they have incentives to ensure that action plans are implemented and that the project appears to be moving forward and producing results.

In many cases, the staff available to undertake a response may be nonnegotiable, based on who is then available. However, if possible, identify people with relevant skills and experience to implement the initiative. Furthermore, people with a good network of contacts in partner organizations can prove extremely useful, as it can mean the formal lines of communication between agencies can be circumvented, thereby getting the job done more quickly, and possibly with less potential for a refusal to cooperate. In addition, local knowledge of an area and the people that live there can prove useful for dealing with problems on the ground. In short, don’t under–estimate the importance of informal contacts.

When current staff are not available and budgets allow, it may be necessary to recruit new project staff. This has frequently been shown to take longer than anticipated, with a recruitment process’ often taking six to nine months before the candidate starts work. This can have a detrimental impact on an initiative’s timing, especially if implementation cannot begin until that staff member is in place.

Many positions will be funded on short-term contracts, and this creates uncertainty for staff funded in this way. One can usually expect a staff member to start looking for a new job six months before the contract termination. This can create problems of continuity if the staff member leaves some months before the end of the project, as there is likely to be insufficient time to recruit a new staff member. In turn, this can affect the degree of implementation that can be completed.

For agencies large enough to justify the cost, it may be preferable to hire and develop permanent support staff who have the necessary knowledge, skills. and abilities for problem–oriented projects. The permanent support staff should then be able to manage most projects internally, and even if external aid is needed, the permanent staff can work with the external staff to help ensure continuity.

† For a discussion of the knowledge, skills, and abilities required for effective problem analysis and management, see Boba (2003) [PDF].

Before taking steps to implement responses, you should first carefully plan the implementation process. It is all too easy to become impatient to get on with the job of tackling the problem, and neglect to spend time on planning how to implement it. This is akin to setting out to build a house without first working out how big it’s going to be, where the walls are going, or what order the work needs to be done in! Yet planning is an extremely important part of the response activity. It can prevent making mistakes that could subsequently prove expensive, either in terms of time, effort, costs, or reputation.

This section examines some of the key points you need to consider when planning to implement a response.

Consider introducing a project management framework, or at least drawing on project management principles in planning and implementing a response. 19 Project management principles help to define a way of working that is particularly relevant to POP initiatives. These include the following:

Project management is therefore a dynamic role that requires a degree of leadership, ingenuity, and risk to see a project through to a satisfactory conclusion.

You should view project management as more than simply a form-filling exercise. There is some paperwork required to maintain accountability, and to be used as a record of decisions made and so forth, but you should see it more as a mindset. It is a way of thinking and working that involves careful planning and regular checking to ensure the implementation process remains on track. If you miss this point, then there is a danger that project management becomes a bureaucratic process that stifles implementation, rather than assisting it. See the appendix for a sample project management form used in a POP initiative. There are also many useful project management software programs available.

The purpose of goals and objectives is to define the initiative. They state the end result to be sought and set out what is to be achieved along the way. You can also use them as a reference point for checking that the initiative remains on track, by ensuring that the undertaken activity is conducive to meeting the goals and objectives. The following section looks at goals and objectives in turn.

Ideally, a project goal should specify the problem to be tackled. While this sounds obvious, all too often projects fail to specify a goal, or specify it in terms of the activity to be undertaken rather than the problem to be solved. Examples of this might be “to undertake a project to target prolific offenders,” or “to undertake a project to build youth shelters in local parks.” The problem with these process–oriented approaches to specifying goals is that they can be achieved without having any impact on the problem they set out to address. For example, a project aimed at targeting prolific offenders with enforcement activity and intensive support may be successful in the sense that it has identified the right people and engaged them in enforcement programs and support, but may not change their individual offense levels. In such circumstances, the project has successfully delivered its intervention, but has failed to affect the problem. From a POP perspective, you should view such projects as failures, since the problem persists.

Goals should therefore be problem–oriented, specifying the problem that will be addressed. Specifying a clear, problem-oriented goal in this way can help to prevent “mission creep,” in which a project that originally sets out to address one problem subsequently has other issues added to it. A clear project goal should therefore help to maintain a focus.

A clear statement of the problem leads to a clear goal. For example, when the problem is understood to be “vehicle crashes caused by excessive speed,” one would expect the goal to be “to reduce the number or severity of vehicle crashes,” not “to increase enforcement of speeding laws,” nor even necessarily “to reduce speed.” Clarity in the goal enables sensible adjustments to the response plan if one particular response does not appear to be effective. So, in the vehicle crash example, if enforcing speeding laws does not appear to be reducing crashes, you should try a response other than enforcing speeding laws, before the project is deemed a failure.

A word of caution is in order about setting quantified targets, whether internally or externally imposed. Examples of such targets might include to reduce the area’s extent of vehicle crime by 15 percent, or to reduce the rate of violence against the person to the national average. However, there is the question over how such targets are set. These are often based on a professional judgment about what can be achieved. Often they are simply imposed by funding organizations. They are seldom based on careful data analysis. However, failure to meet targets can demoralize staff involved in delivering a project, even if the project has nonetheless achieved other positive (yet unmeasured) outcomes.

Perhaps the most problematic aspect of targets is that they generally fail to take into account the counterfactual. Yet this is extremely important in POP initiatives. The fact that a project meets its outcome target does not necessarily imply success if you expected to achieve a greater reduction (based on what has been achieved elsewhere). Furthermore, failure to achieve the project outcome is not necessarily a negative result if you actually expected to achieve a worse result. To illustrate this point, a recent evaluation of the U.K. Arson Control Forum’s New Projects Initiative estimated that the combined effect of 19 arson reduction projects was an 8 percent increase in deliberate primary fires. 21 However, this was a much better performance than in a series of comparison areas, which witnessed a 27 percent increase in deliberate primary fires. On this basis, the program was shown to be very cost–effective, yet if a simple arson reduction target had been used, the program would have appeared a failure.

While goals should be outcome– and problem–focused, objectives should be output– and intervention–focused. They should specify what you are actually going to undertake as a response, and preferably how much you will undertake. For example, a project goal may be “to reduce thefts from vehicles in an area,” while two objectives may be “to provide an additional 100 hours of high–visibility patrol in hot-spot areas” and “to notify all vehicle owners who leave items on display in their vehicles.” Although people often use such terms as “goals,” “objectives,” and “targets” interchangeably and with much confusion about the proper distinction among them, it is mainly important to bear in mind the need to distinguish between what you are trying to achieve (the purpose of the initiative) and how you are trying to achieve it (the means toward the end).

At an early stage in response development, it is likely that one or more responses will emerge as intervention favorites. Indeed, the most suitable response will often appear obvious to those planning implementation. Nevertheless, it is worth asking the following 10 questions about any planned intervention:

† See Goldstein (1990: pp. 141-145) [PDF] for further discussion of factors to consider in choosing from among response alternatives.

† See the Response Guide titled The Benefits and Consequences of Police Crackdowns [PDF] for further discussion of this issue.

It is also important to consider how long it takes to implement the intervention. For example, high–visibility police patrolling takes as long as the patrolling itself. By contrast, the apparently simple intervention of blocking an alley to the rear of houses with a set of gates has been shown to take, on average, a year to complete in the United Kingdom. 27

Once you have selected responses, you should pay careful attention to how long the response implementation will take. There are a number of reasons for this:

Most of us pay little attention to the timetables required for a response, and calculate these in one of two ways. We either pick a time off the top of our head, based on a rough calculation of how long the most salient tasks will take, or we think of a deadline first and then fit the tasks into the available time. From a planning perspective, neither is sufficient, as both allow for the possibility of significant time overruns.

A preferred approach to developing a realistic timetable is to produce a Gantt chart using the following “key stage” approach:

The point of undertaking this exercise at the planning stage is that, by taking a little time to work out how long it is likely to take, you can plan how to complete the project more quickly or to change directions before incurring implementation expenses and having to make changes while the response is in progress.

At the planning stage, you should also consider the implementation risks faced in the response. In identifying risks, you should pay particular attention to those that are most closely related to a response (for example, one could highlight and plan for the risk of being hit by a meteorite, but the chances of that happening are slim), and about which one can do something. You should consider risks in terms of both the likelihood of occurrence and the impact they will have on the response, using the risk matrix shown in Figure 2. Pay particular attention to those where the likelihood and risk of occurrence are highest. Risks can also be divided into two kinds-those associated with implementation failure, and those associated with theory failure (for example, the mechanism of change does not operate as expected).

| Impact on Project | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood of Occurrence | ||||

| Low | Medium | High | ||

| Low | Low risk | Medium risk | High risk | |

| Medium | Low risk | High risk | Immediate action | |

| High | Medium risk | High risk | Immediate action | |

Figure 2. Risk Matrix.

The table below provides an example of a risk analysis undertaken in relation to a project to install a CCTV system. This shows the risks that have been identified, their likelihood of occurrence, their impact, and proposed actions to address them.

Table. Example of a Risk Analysis

| Risk | Likelihood of Risk | Impact of Risk | Action to be Taken |

| The CCTV system does not provide adequate coverage due to a limited number of cameras. | Low | High | In drawing up the specifications, ensure that sufficient camera sites are identified. |

| The camera pictures’ resolution is insufficient to identify people. | Low | Medium | Test the cameras’ resolution before making a final decision on the system. |

| It proves difficult to maintain the system in the future. | Medium | Medium | Produce a plan for how the system will be maintained and for its associated costs. |

Once you have identified risks, you can take a number of approaches to deal with them, including the following:

As part of the response planning stage, you should draw up an action plan that details what is to be undertaken, how it is to be undertaken, who is to be involved, and over what time periods it will be undertaken. The list below provides an outline of what might be included in this action plan:

The action plan provides an opportunity to share your ideas about how the response will be undertaken, and to identify changes you should make before the implementation process starts. This is an extremely important part of the process, as by sharing the plan, you can obtain “buy-in” from stakeholders, as well as take on board the perspectives of others who may help to shape a more effective response.

The implementation process involves getting the work done. Much of what will be undertaken at this stage will depend on the nature of the selected response. However, there are some generic points that can be made about implementation. Probably the most important point is that implementation should start as soon after the planning has been completed as possible. There are several reasons for this:

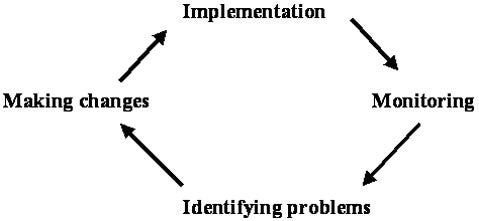

You can view the implementation process as a recurring process, as outlined in Figure 3. Initiatives seldom run smoothly from start to finish as planned–they nearly always involve changes. Once response implementation has begun, you should monitor it to identify obstacles as they emerge, and to make changes to the response so that the implementation process can continue. This approach should help to prevent implementation failure by helping you to identify problems that need to be addressed at the earliest opportunity and take the necessary action to keep the response on track.

Figure 3. Iterative Implementation Process

Monitoring is all too often seen as something that is imposed by others external to the implementation process. This is particularly the case where funding is received from external partners who impose their own monitoring systems to ensure their funding is being spent appropriately. In such cases, it is often not unusual for the funding agency's monitoring to be the only form of monitoring undertaken. However, this may not meet the response team’s needs as a means of identifying problems and making changes. You should pay careful attention to establishing monitoring systems that will reflect the reality of the implementation process and provide timely and meaningful measures.

The extent to which detailed monitoring systems are required will largely depend on the response leader’s level of involvement. If the leader takes a hands–on approach to delivering the response, then a less detailed form of monitoring will be required than if that person is more removed from the day–to–day delivery process.

You should address a number of factors in the monitoring, and these will largely focus on the “constraints” noted earlier—time, costs, other resources, and quality. Issues to consider in monitoring include the following:

† See Problem–Solving Tools Guide No. 1 [PDF], Assessing Responses to Problems, for an in–depth discussion of measuring the impact of responses on problems.

Making some changes in the response plan is to be expected. If problems exist, then you should address them promptly. There are two routes to making changes, which depend on the nature of the problems that are experienced–replanning and redesigning:

Once you have completed the response implementation, consider what will happen afterwards. In some cases, interventions require no follow–up activity, and the problem is resolved with no further action required. In other cases, it is necessary to plan what will happen to interventions once the response ceases. There are a number of ways to exit from responses:

In considering the exit strategy to pursue, you should address a number of questions:

The final stage in the implementation process is the learning process that you should associate with responses. The SARA methodology’s assessment stage usually focuses on understanding the extent to which the response has addressed the problem, so that this can be fed into subsequent scanning and analysis. It is, however, important to capture the learning from the response stage for future implementation. The process of implementing interventions usually brings with it a great deal of knowledge and experience, which will be transferable to either other assignments, or to implementing the same responses in other contexts. All too often, this knowledge and experience resides with the response team’s individual members and is not shared with the wider organization. This means that organizational memory about particular interventions can be short, and there can be danger that mistakes made in implementation are repeated time again because the response knowledge is not disseminated.

Consider therefore finding ways of extending the knowledge gained from implementing responses to others within the organization. This may be through debriefing sessions with response staff, presentations, or process–oriented evaluations of the responses. Regardless of the approach taken, you should attempt to add to the working knowledge of interventions in future responses.

1 See, for example, Skogan et al. (2000) [Full text]; Scott (2000) [Full text]; Goldstein (1990); Sparrow (1988); Laycock and Farrell (2003) [Full text]; Greene (1998); Rosenbaum (1994); Grinder (2000); Eck and Spelman (1987).

2 Goldstein (1990); Eck and Spelman (1987); Capowich and Roehl (1994); Scott (2000) [Full text].

3Goldstein (1990).

4See, also, Scott (2006).

5Bullock, Farrell, and Tilley (2002) , citing Read and Tilley (2000). [Full text]

6Long et al. (2002).

7Goldstein and Susmilch (1982). [Full Text]

8Goldstein and Susmilch (1982). [Full Text]

9Eck and Spelman (1987).

10Laycock and Tilley (1995).

11Kennedy, Braga, and Piehl (2001). [Full text]

12Hamilton-Smith (2004). [Full text]

13McGarrell, Chermak, and Weiss (2002). [Full text]

14Sutton (1996) [Full text].

15Lauderhill Police Department (1996). [Full text]

16Skogan et al. (2000) [Full text].

17Aguirre (2005).

18Brown et al. (2005).

19Brown (2006). [Abstract only]

20Goldstein and Susmilch (1982). [Full Text]

21Brown et al. (2005).

22Pawson and Tilley (1997).

23Pawson and Tilley (1997).

24Larson (1980).

25Tilley et al. (1999) [Full text].

26 See, for example, Schweinhart and Weikart (1993).

27Johnson and Loxley (2001). [Full text]

28Brown and Clarke (2004). [Abstract only]

Aguirre, B. (2005). “To Serve, Protect–With Proof: Fremont Police, Looking To Cut Costs, Will Soon Stop Responding to Burglar Alarms Without Knowing if a Crime Has Been Committed.” Inside Bay Area, January 20.

Boba, R. (2003). Problem Analysis in Policing. Washington, D.C.: Police Foundation and Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. [Full Text]

Brown, R. (2006). "The Role of Project Management in Implementing Community Safety Initiatives." In J. Knuttson and R. Clarke (eds.), Putting Theory to Work: Implementing Situational Crime Prevention and Problem–Oriented Policing. Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 20. Monsey, N.Y.: Criminal Justice Press. [Abstract only]

Brown, R., and R. Clarke (2004). "Police Intelligence and Theft of Vehicles for Export: Recent U.K. Experience." In M. Maxfield and R. Clarke (eds.), Understanding and Preventing Car Theft. Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 17. Monsey, N.Y.: Criminal Justice Press. [Abstract only]

Brown, R., M. Hopkins, A. Cannings, and S. Raybould (2005). Evaluation of the Arson Control Forum’s New Projects Initiative Final Report: Technical Annex. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. Accessible at

Bullock, K., G. Farrell, and N. Tilley (2002). "Funding and Implementing Crime Reduction Initiatives." RDS Online Report, 10/02. London: Home Office. Retrieved May 25, 2005, from Center for Problem–Oriented Policing website

Capowich, G., and J. Roehl (1994). "Problem–Oriented Policing: Actions and Effectiveness in San Diego." In D. Rosenbaum (ed.), ,The Challenge of Community Policing: Testing the Promises. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Eck, J., and W. Spelman (1987). Problem–Solving: Problem–Oriented Policing in Newport News. Washington, D.C.: Police Executive Research Forum.

Goldstein, H. (1990). Problem–Oriented Policing. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.[Full text]

Goldstein, H., and C. Susmilch (1982). Experimenting With the Problem–Oriented Approach to Improving Police Service: A Report and Some Reflections on Two Case Studies. Vol. 4 of the project on development of a problem–oriented approach to improving police service. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Law School. Retrieved May 25, 2005, from Center for Problem–Oriented Policing website: [Full Text]

Greene, J. (1998). "Evaluating Planned Change Strategies in Modern Law Enforcement: Implementing Community–Based Policing." In J. Brodeur (ed.), How To Recognize Good Policing: Problems and Issues. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications and Police Executive Research Forum.

Grinder, D. (2000). "Implementing Problem–Oriented Policing: A View From the Front Lines." In C. Solé Brito and E. Gratto (eds.), Problem–Oriented Policing: Crime– Specific Problems, Critical Issues, and Making POP Work, Vol. 3. Washington, D.C.: Police Executive Research Forum.

Hamilton–Smith, N. (2004). The Reducing Burglary Initiative: Design, Development, and Delivery. Home Office Research Study 287. London: Home Office. [Full text]

Johnson, S., and C. Loxley. (2001). Installing Alley–Gates: Practical Lessons From Burglary Prevention Projects. Briefing Note 2⁄01. London: Home Office. [Full text]

Kennedy, D., A. Braga, and A. Piehl (2001). "Developing and Implementing Operation Ceasefire." Reducing Gun Violence: The Boston Gun Project’s Operation Ceasefire. Research report. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. [Full text]

Larson, J. (1980). Why Government Programs Fail: Improving Policy Implementation. New York: Praeger Publishers.

Lauderhill Police Department (1996). "Mission: Mission Lake Plaza. Combating an Open–Air Drug Market in a Shopping Complex." Submission for the Herman Goldstein Award for Excellence in Problem–Oriented Policing. Retrieved May 25, 2005, from Center for Problem–Oriented Policing website: [Full text]

Laycock, G., and G. Farrell (2003). "Repeat Victimization: Lessons for Implementing Problem–Oriented Policing." In J. Knutsson (ed.), Problem–Oriented Policing: From Innovation to Mainstream. Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 15. Monsey, N.Y.: Criminal Justice Press. [Full text]

Laycock, G., and N. Tilley (1995). "Implementing Crime Prevention." In M. Tonry and D. Farrington (eds.), Building a Safer Society: Strategic Approaches to Crime Prevention. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Long, J., W. Wells, and W. De Leon-Granados (2002). "Implementation Issues in a Community and Police Partnership in Law Enforcement Space: Lessons From a Case Study of a Community Policing Approach to Domestic Violence." Police Practice and Research 3(3): 231-246.

McGarrell, E., S. Chermak, and A. Weiss (2002). Reducing Gun Violence: Evaluation of the Indianapolis Police Department’s Directed Patrol Project. Research report. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. [Full text]

Pawson, R, and N. Tilley (1997). Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage.

Read, T., and N. Tilley (2000). Not Rocket Science? Problem–Solving and Crime Reduction. Crime Reduction Research Series. Paper No. 6. London: Home Office Policing and Reducing Crime Unit. [Full text]

Rosenbaum, D. (1994). The Challenge of Community Policing: Testing the Promises. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Schweinhart, L., and D. Weikart (1993). A Summary of Significant Benefits: The High⁄Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 27. Ypsilanti, Mich.: High⁄Scope Press.

Scott, M. (2006). "Implementing Crime Prevention: Lessons Learned From Problem–Oriented Policing Projects." In J. Knuttson and R. Clarke (eds.), Putting Theory to Work: Implementing Situational Crime Prevention and Problem–Oriented Policing. Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 20. Monsey, N.Y.: Criminal Justice Press.

–––(2000).Problem–Oriented Policing: Reflections on the First 20 Years. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. [Full text]

Skogan, W., S. Hartnett, J. DuBois, J. Comey, M. Kaiser, and J. Lovig (2000). Problem–Solving in Practice: Implementing Community Policing in Chicago. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. [Full text]

Sparrow, M. (1988). "Implementing Community Policing." Perspectives on Policing, No. 9. Cambridge, Mass., and Washington, D.C.: Harvard University and U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice.

Sutton, M. (1996). Implementing Crime Prevention Schemes in a Multiagency Setting: Aspects of Process in the Safer Cities Program. Home Office Research Study 160. London: Home Office. [Full text]

Tilley N., K. Pease, M. Hough, and R. Brown (1999). Burglary Prevention: Early Lessons From the Crime Reduction Program. Crime Reduction Research Series. Paper No. 1. London: Home Office. [Full text]

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: askCopsRC@usdoj.gov

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.