Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

The Problem of Student Party Riots

Alcohol-related riots among university students pose a significant problem for police agencies that serve college communities.§ The intensity of the disturbances may vary. However, the possible outcomes include property destruction and physical violencea serious threat to community and officer safety.

§ In this guide, we use the terms university, college, and school interchangeably to refer to institutions of higher learning.

Since student party riots are relatively rare, we know little about what causes them. In addition, it has been difficult to gauge the effectiveness of police interventions. Despite these limitations, the available evidence suggests that the most promising strategies for addressing the problem are multifaceted and include partnerships with the university and the surrounding community. Developing a comprehensive action plan requires a thorough understanding of the characteristics of student gatherings, and of the particular interventions likely to have the greatest impact.

This guide provides a framework for understanding student gatherings.§§ You can use this framework to systematically investigate your local problem of student party riots. You can also use it to develop a wide range of proactive strategies to reduce the potential for student violence and other misconduct. In addition, this guide summarizes interventions used to control past disturbances. You can use these interventions, along with the solutions you develop, to create a comprehensive strategy for addressing your problem.

§§ Following the work of McPhail and Wohlstein (1983) [PDF], we prefer the term gathering to crowd, since the latter tends to imply a large group acting in unison, without individual agendas.

Problem Description

Student party riots are often associated with a college sport team's victory or loss. However, disorderly group behavior can also occur during large street parties unrelated to a sports event. Regardless of the initial reason for a gathering,§ some gatherings end with intoxicated students' engaging in destructive behavior.§§

§ For the purposes of this guide, a gathering is a group of 25 or more students with access to alcohol (Shanahan 1995) [PDF]. However, 25 should serve as a general rule of thumb, rather than an absolute minimum.

§§ There is no standard term for the problem this guide addresses. Some people use the name "celebratory riots," but this trivializes the outbursts, and many of them are not celebrations of anything in particular. Four characteristics define these problems: they take place on or near college campuses; most of the participants are university students; these students, and others, drink a lot of alcohol; and the events range in intensity from noisy parties to serious riots with injuries and property damage. One possibility was to call these problems USARDs, for University Student Alcohol-Related Disturbances. Even though that term accurately describes the problem, it is awkward and hard to remember. Student party riots is brief, clearly conveys the basic idea, and is easily understood.

In some jurisdictions, creating such disturbances becomes a "tradition" among students. For example, on or around May 5 each year, University of Cincinnati students attend a Cinco de Mayo celebration that often results in rioting.[1] Madison, Wisconsin, police prepare for an annual Halloween celebration that has, in the past, ended in clashes between students and officers.[2] In Columbus, Ohio, the risk of a riot increases following a football game between Ohio State University and the University of Michigan. These and similar events tend to attract more and more students and other revelers each year, which in turn can lead to larger gatherings that end in more violence and destruction. Thus it is imperative that police not let a single riotous event become a student tradition.

Student party riots tend to share the following characteristics:

- A lot of intoxicated people are present

- Both males and females are present, and nearly all the attendees are young adults

- The gathering includes students from other universities

- The gathering includes young adults who are not college students

- The disturbance starts late at night and continues into the early morning

- Males are most often responsible for any destructive acts

- Injuries and property damage (e.g., from fires and overturned cars) are common

- Participants resist authority/police intervention[3]

Related Problems

Along with student party riots, police face other youth-disorder problems, ones not directly addressed in this guide. The following require separate analyses and responses:

- Disturbances during political protests

- Graffiti

- Vandalism

- Underage drinking

- Crowd control in stadiums and other public venues

- Drunken driving

- Noise complaints in residential areas

- House parties

- Disorderly conduct in public places

Factors Contributing to Student Party Riots

Understanding the factors that contribute to your problem will help you frame your own local analysis questions, recognize key intervention points, select appropriate responses, and determine effectiveness measures.

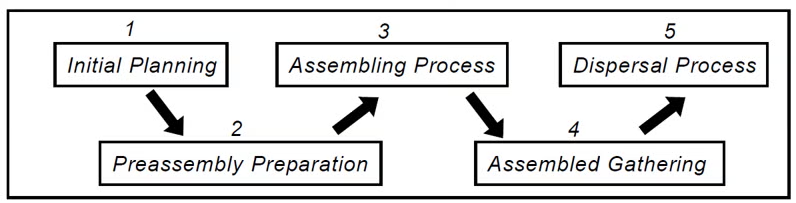

What We Know About the Structure/Characteristics of Student Gatherings

Most gatherings are not completely spontaneous:[4] some degree of planning is typically required to bring a lot of people together. Furthermore, gatherings have a "life cycle" that consists of at least five discernable stages: (1) initial planning, (2) preassembly preparation, (3) assembling process, (4) assembled gathering, and (5) dispersal process (see figure).§ Once police determine that a student gathering is in the works, they can reduce the likelihood of disorderly behavior by applying a number of prevention strategies at each stage.

§ The five-stage student-gathering model in this guide is an extension of McPhail's work. McPhail (1991) suggests that temporary gatherings have a life cycle that includes an assembling process, the assembled gathering, and a dispersal process. The model presented here encourages police to develop intervention strategies targeting earlier stages in the process.

Figure 1: Five stages of a gathering's "life cycle."

Stage 1: Initial planning. A few students decide to host a party. They decide whom to invite, how to invite them, when and where to hold the party, what activities (if any) the party will include, and what they need to do to make it happen. The length of this planning stage may vary greatly. Some gatherings may occur with little forethought, such as when students go to a popular bar after a big sports event. However, students may plan other gatherings a year or more in advance.[5] They may choose party locations either hastily or carefully. Similarly, invitations can come via flyers posted months in advance, word of mouth, or simple cues that indicate people are gathering nearby. The more students are aware of when and where gatherings are likely to occur, the more spontaneous the gatherings will appear; little advanced planning and communication is needed if students regularly gather at a particular location after an event. The more frequently the gatherings occur, the more predictable they become, and the less effort is needed for future planning.

Stage 2: Preassembly preparation. Alcohol, typically obtained by the hosts or the guests within a few days or hours of a scheduled event, plays a significant role in student party riots. Obtaining alcohol is only one of several possible tasks done during the preassembly preparation. Students may also decorate, talk with friends or neighbors, or gather belongings to take with them to the event. They may even give one another last-minute notice of any possible police presence. The length of this stage will depend on the degree of planning or spontaneity involved.

Stage 3: Assembling process. In the assembling process, people head for the gathering. Their transportation methods are of interest. They may drive alone or with friends, walk, take a taxi or bus, or simply step out of their front doors and into the street. Transportation can affect several aspects of the gathering, including who can attend and how long it lasts. Transportation also has implications for the final stage.

Stage 4: Assembled gathering. The assembled gathering usually receives the most media, police, and other attention. It may be easy to forget that most gatherings, including student gatherings, remain orderly.[6] People tend to congregate in small groups and spend most of their time talking and observing others similarly engaged.[7] However, with a gathering that turns violent, signs of disorderly behavior usually surface sometime near the end of it, after participants have drunk a lot of alcohol. The disturbance is likely to carry over into the next stage.

Stage 5: Dispersal process. Transportation methods are again important during the dispersal process. During this stage, the police must encourage movement away from the gathering, while preventing the spread of vandalism and violence to nearby areas as people leave the site. During a student riot, police may find themselves trying to disperse drunken participants. Drunken driving may become a problem at this stage if students have used their own vehicles to get to the gathering.

What We Know About Students Who Participate in Riots

Contrary to what some police officials believe, we know that crowds do not drive individuals mad, nor do individuals lose cognitive control.§ Experts who have systematically studied gatherings have discredited "madding crowd" theories.[8] Crowd members make their own choices. That is not to say that crowds do not appear to have a will of their own, or that individuals do not often use the crowd as an excuse for their behavior. However, while people may be influenced by others' actions, there is no evidence to suggest that people lose the capacity to control their own behavior simply because others are present.

§ One police official was quoted as saying, "Because the mob mentality makes meaningful discussion impossible, and because the members are no longer guided by rational thought, it is critical to avoid any situation that may be misinterpreted." (Begert 1995)

We also know that most students who attend gatherings that result in riots do not behave destructively. Participants at such gatherings attend for a variety of reasons. In a telephone survey of 1,162 Michigan State University students,[9] the top reasons given for attending gatherings were to have fun (65 percent), to meet up with friends (60 percent), and to celebrate (40 percent). Only 5 percent of students said the main reason they party is to get drunk. Other students attend celebrations just to witness them. It has been reported that as many as 50 to 60 percent of attendees are there only to observe.[10]

Those who attend gatherings to cause destruction—and who are of greatest police concern—usually make up the smallest portion of an assembly. University of Cincinnati students were surveyed in 2004 about their experiences at the annual Cinco de Mayo off-campus celebrations.[11] Less than 1 percent of respondents who attended said they destroyed property, and only 1.4 percent said they had engaged in a confrontation with Cincinnati police during the street riots that followed the celebration. These numbers correspond with photos and eyewitness accounts of the event.

Why Some Students Engage in Physical Violence and Property Destruction

Unfortunately, research has been unable to provide a clear profile of the type of person likely to engage in violence at university student gatherings.[12] Given the general characteristics of university students, we know that most attendees, and therefore those who engage in violence, are young adults. Media photos and police records indicate that males are more likely than females to be observed and arrested for committing acts of violence and vandalism. However, this information does not explain why some students engage in physical violence and property destruction, while others do not.

Student party riots often include people who do not attend the university nearest to the gathering. It has been suggested that these individuals are more likely to engage in disruptive behavior. Though this is plausible, since such people have fewer stakes in the university community, no research addresses this issue. We must also be cautious, as "outsider" explanations can be used to shift blame.

Instead of focusing on who, we might ask why students engage in destructive behavior. When a relatively orderly gathering suddenly turns violent, it is referred to as a "flashpoint."[13] It is imperative that police be familiar with and recognize factors that can contribute to a flashpoint.

It has been suggested that boredom or a lull in activity may create the impetus for a violent flashpoint.[14] When the initial excitement of the event has passed (e.g., the team has won or lost, or midnight has passed on New Year's Eve), but dispersal fails to begin, some individuals may want to renew the excitement at the gathering. They will create a new focal point to create or maintain the momentum of the gathering. The new focal point may consist of a few people burning, looting, or otherwise vandalizing property.

While most members of a gathering do not directly participate in riotous behavior, these "nonparticipative" members may further instigate such activity through their mere presence. Typically, as the riotous behavior begins, two simultaneous movements, or surges,[15] occur within the gathering: people move toward those engaged in destructive behavior, and others move away. Those who do not participate in disorder but stay to watch can provide tacit or open support for those engaged in destructive behaviors.[16] This helps to sustain the behavior of the violent minority, while making it difficult for police to remove those causing the disruption and to disperse the gathering.

The Role of Alcohol in Student Party Riots

There is a large and growing body of research that tells us there is a strong correlation between alcohol use and violence and vandalism committed by university students. Research studies show that compared with nondrinking students, students who drink excessively have higher rates of injuries, assaults, academic problems, arrests, vandalism, and other health and social problems.[17] Student surveys and police records have also found a correlation between student drinking and property destruction,[18] vandalism,[19] and violent crime[20] on campus.

While quantitative research and anecdotal evidence may seem to suggest alcohol causes students to become violent and damage property,[21] we must be careful when attempting to interpret these findings. Not all students who get drunk engage in such activities. Much like crowds do not drive people "mad," nor does alcohol drive students to commit crime.

Drinking a lot of alcohol can, however, impair the judgment of people who may already be predisposed to reckless behavior. It has been established that excessive drinking can cause people to act overconfidently and carelessly, lose awareness of their surroundings, and react violently to people they perceive as offensive.[22] This helps to explain why some students, while in the presence of police or other authority figures, continue to vandalize property, become hostile with others, or fight, and fail to disperse when asked to do so.

The Role of Police in Student Party Riots

There is a general consensus among those who study gatherings regarding the importance of police action. Researchers and practitioners agree that the police usually play a significant role in forestalling or provoking disorder.[23] Interviews with officers who have responded to riots suggest that police can escalate—or even initiate—conflict by treating all members of a disruptive gathering as equally dangerous.[24] This guide presents techniques that emphasize the importance of distinguishing between individuals and subgroups within a gathering.

Another important lesson learned from case studies of student party riots is that planning is key. Proactive efforts yield more consistent and desirable results than reactive enforcement methods. Implementing multiple interventions at each of the five stages of a gathering's "life cycle" will help to prevent student misconduct and subsequent police use of force.

Summary of Factors Contributing to Student Party Riots

- Student gatherings are made up of five discernable stages. Each stage provides an opportunity for intervention efforts.

- Gatherings or crowds do not drive people mad or make them lose control. Students who attend gatherings have a wide variety of personal agendas, and typically only a small minority will participate in disorderly behavior.

- A flashpoint is the moment a gathering turns violent. A flashpoint is likely to occur after the initial reason for celebrating has passed, and immediate dispersal fails to begin. Those who stay to watch the disturbance often help to prolong the disorder, even without direct participation.

- Alcohol consumption, especially of large quantities, can help to initiate or exacerbate disorder in student gatherings.

- Some types of police action can prevent disorder, and other types may provoke it. Proactive responses are more likely to prevent a disturbance than reactive responses.

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Student Party Riots

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

Your E-mail *

Copy me

Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.