The Implementation Process

The implementation process involves getting the work done. Much of what will be undertaken at this stage will depend on the nature of the selected response. However, there are some generic points that can be made about implementation. Probably the most important point is that implementation should start as soon after the planning has been completed as possible. There are several reasons for this:

- If a problem exists, it is right that a response should be put into practice as soon as possible to alleviate that problem.

- The interest and good will generated at the planning stage should not be squandered through implementation delays. Act before stakeholders change their minds!

- The sooner you start implementing a response, the sooner you will be aware of implementation problems, and therefore the sooner you can address them.

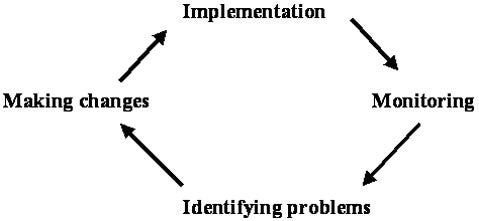

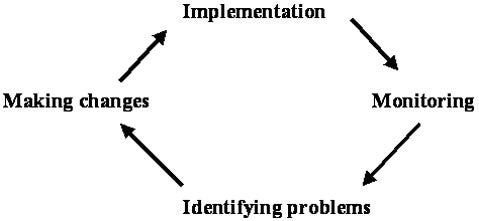

You can view the implementation process as a recurring process, as outlined in Figure 3. Initiatives seldom run smoothly from start to finish as planned–they nearly always involve changes. Once response implementation has begun, you should monitor it to identify obstacles as they emerge, and to make changes to the response so that the implementation process can continue. This approach should help to prevent implementation failure by helping you to identify problems that need to be addressed at the earliest opportunity and take the necessary action to keep the response on track.

Figure 3. Iterative Implementation Process

Monitoring Responses and Identifying Problems

Monitoring is all too often seen as something that is imposed by others external to the implementation process. This is particularly the case where funding is received from external partners who impose their own monitoring systems to ensure their funding is being spent appropriately. In such cases, it is often not unusual for the funding agency's monitoring to be the only form of monitoring undertaken. However, this may not meet the response team’s needs as a means of identifying problems and making changes. You should pay careful attention to establishing monitoring systems that will reflect the reality of the implementation process and provide timely and meaningful measures.

The extent to which detailed monitoring systems are required will largely depend on the response leader’s level of involvement. If the leader takes a hands–on approach to delivering the response, then a less detailed form of monitoring will be required than if that person is more removed from the day–to–day delivery process.

You should address a number of factors in the monitoring, and these will largely focus on the “constraints” noted earlier—time, costs, other resources, and quality. Issues to consider in monitoring include the following:

- The delivery deadline. Probably the most common area for problems to emerge is in terms of slippage in the delivery deadline, which can occur in a multitude of ways. You should monitor this carefully to ensure the response remains on track, or to revise expectations about how long the delivery will take to complete.

- The response costs. With finite resources, you will need to ensure that the available funding is spent as planned, and that costs do not rise above that which can be managed within the initiative.

- The staff time devoted to the response. Pay attention to the amount of time that staff are devoting to a project, to ensure they are not working excessive hours and there are sufficient staff to complete the task within the available time.

- Blockages and brakes on the implementation process. Sometimes a response can be delayed due to a problem in the implementation process. This can be a blockage to delivery, such as when an external partner fails to undertake tasks that are essential to the next implementation stage, or a brake to delivery, such as when essential tasks take longer than anticipated. This may require examining each stage of the implementation process to identify whether blockages and brakes can be eliminated, circumvented, or fixed.

- Adverse reactions to the response. Responses can lead to adverse reactions from stakeholders, including others in your organization, partner organizations, response recipients, and the local community. Part of the response implementation process will be to manage relationships with key stakeholders to ensure they are kept on side, and to be receptive to the concerns they may have about the way in which a response is being undertaken.

- Unintended consequences. Regardless of the planning that is undertaken, sometimes there are unexpected and unintended consequences that result from the response. Where these consequences are negative (such as displacing the problem), consider how to address them with the existing resources. Some unintended consequences can be acceptable if the positive gain from the response outweighs the negative aspects. For example, there is seldom 100 percent geographic displacement resulting from a response, and this means there will still be a net gain from the response.

- The impact on the original problem. Determine whether the response is addressing the problem it set out to tackle. Obviously, for many responses there will be lag in terms of impact following intervention, which may make it difficult to judge effectiveness during the implementation process. However, where an impact is expected within the life of the implementation yet no impact is observed, it may be necessary to reconsider the intervention selected or to examine whether there are ways of increasing its effectiveness.

Making Changes

Making some changes in the response plan is to be expected. If problems exist, then you should address them promptly. There are two routes to making changes, which depend on the nature of the problems that are experienced–replanning and redesigning:

- Replanning is the most common form of change resulting from a response. This will result from problems such as time delays, cost overruns, and system blockages. They require immediate decisions to be made to "tweak" the system to get the implementation back on track. They require you to revisit the original plan and work out how to make modifications to ensure the response is completed as expected. Indeed, this will be part of the normal process of response implementation, in which monitoring identifies problems you must address, which in turn results in replanning of the response so that implementation can continue.

- Redesigning involves more fundamental changes, but is far less common than replanning. This may be necessary if it becomes clear that a planned response is simply unworkable, or where there are negative outcomes that far outweigh the likely positive achievements. Under these circumstances, it may be necessary to halt the response implementation and return to the drawing board, selecting alternative interventions that might be more feasible⁄effective. This should not be viewed as a negative process. Indeed, it is more acceptable to accept that the response is not working and start the process again, than to ignore the response failure and continue with the implementation process regardless of whether it will resolve the problem.

Exit Strategies

Once you have completed the response implementation, consider what will happen afterwards. In some cases, interventions require no follow–up activity, and the problem is resolved with no further action required. In other cases, it is necessary to plan what will happen to interventions once the response ceases. There are a number of ways to exit from responses:

- Closure. Sometimes it will be necessary to stop intervention. In these cases, you should consider whether intervention can be abruptly halted, or whether it is necessary to slowly wind down activity and exit gradually.

- Continued project work. In some cases, you may decide to have the existing team continue to operate the response in its current format. This represents a no–change situation, although you should recognize that such an approach will probably not be sustainable in the long term. This kind of solution is common where additional project funding is obtained to continue the response implementation.

- Handover to partners. It may be possible to hand over the project work for continuation by an external partner who agrees to operate the response similarly to the original approach.

- Mainstreaming. This is perhaps more aspired to than achieved, but in some cases it is possible to translate a response originally undertaken in a project format into an organization’s routine and mainstream activity.

In considering the exit strategy to pursue, you should address a number of questions:

- Has the original problem the response addressed been sufficiently prevented⁄reduced⁄removed?

- What is likely to happen to the problem once the response stops? Do you expect it to reappear?

- What will be the stakeholders' views toward stopping the response?

- If continued response is necessary, can the organization support it financially/politically? Are there other organizations that would be willing⁄able to undertake the response? Would stakeholders accept implementation by these other organizations?

The Learning Process

The final stage in the implementation process is the learning process that you should associate with responses. The SARA methodology’s assessment stage usually focuses on understanding the extent to which the response has addressed the problem, so that this can be fed into subsequent scanning and analysis. It is, however, important to capture the learning from the response stage for future implementation. The process of implementing interventions usually brings with it a great deal of knowledge and experience, which will be transferable to either other assignments, or to implementing the same responses in other contexts. All too often, this knowledge and experience resides with the response team’s individual members and is not shared with the wider organization. This means that organizational memory about particular interventions can be short, and there can be danger that mistakes made in implementation are repeated time again because the response knowledge is not disseminated.

Consider therefore finding ways of extending the knowledge gained from implementing responses to others within the organization. This may be through debriefing sessions with response staff, presentations, or process–oriented evaluations of the responses. Regardless of the approach taken, you should attempt to add to the working knowledge of interventions in future responses.